PUPPETRY OPERATIONAL PROCEDURES & OTHER THOUGHTS

The shadow theatre is a puppet form operated from below, already discussed. But in China (whose shadow theatre is named Ying Xi) and Turkey (whose shadow theatre is named for the popular character Karagoz), they are operated horizontally (the manipulation rods are positioned at a 90-degree angle in relation to the screen). Consequently, some scholars postulated that the Chinese and Turkish shadow theatres were developed independently from India’s or Indonesia’s because the operation of the Chinese and Turkish flat cutouts is dissimilar to the other countries’ method, which is to operate the puppets with rods from below. But in India, we see that the pavaikuttu uses detachable rods that connect to the puppets’ hands when required, and, if the puppeteer is standing while manipulating the hands and arms (a common procedure), the operation is by horizontally held rods, exactly as in China and Turkey. Indeed, all that is required to transform an Indian or Indonesian technique into a Chinese or Turkish technique is for the puppeteer to stand up.

Another puppetry form operated from below is the rod puppet: three dimensional carved figurines manipulated from rods below the “stage.” The “stage” may be a curtain hiding the manipulator who motivates the puppets which appear above the curtain, or a large banana log on the floor on which is planted the puppets, and with the manipulator in full view. This operation with rods (normally with one attached to each of the puppet’s hands, and one rod attached to the body of the figure), is identical to the shadow theatre, indicating its ultimate origin.

In Bengal, India, we have the Putul Nautch, a rod-puppet form. Descriptions of these puppets are reminiscent of automata, and the presentation of these could be a debased form of neurospasta. Indeed, the translation of Putul Nautch is “dancing dolls,” which makes one immediately think of such displays, and so it may be that, in earlier times, these puppets only performed dancing and acrobatic tricks, and not plays. Contractor provides a detailed description:

Bengal is the only place in India that has rod puppets. They are known by the name of Putul Nautch or dancing dolls. They have an individuality of their own in the construction and manipulation. Yet in the sculpting, a primitive yet effective method is used, very similar to the rod and string puppets of the Puebla and Ocotlan Red Indian Tribes of U. S. A., who used corn husk and clay. Rice husk and clay is used for the Bengal Rod Puppets.

The Bengal puppets are about 1½ metres in height and are built over bamboos [i.e., long poles extending down] 2½ meters long. The body and limbs have a bamboo base, which was originally covered and plastered with hay and rice husk mixed with clay to give the required shape. The finishing was then done with a smooth coating of banana leaf. When dry they were finally painted in bright colours and then clothed. This very old method of construction can no longer be seen; instead, one comes across entirely wooden puppets on a bamboo prop. The body part is not of solid wood, but carved or scooped out from the back and hollowed. The arms of these puppets are manipulated by a common string for both arms [passing through the body] and rods projecting from the elbows, which act like a lever. They have no legs, so the lower portion of the body is always covered by the sari or dhoti that is draped around them. There is also some hip movement in these puppets produced by a straw loop just below the waist. This loop often gives incidental movement, but can otherwise be moved from under the covering garments.

In manipulating the Putul Nautch puppets, the puppeteers first tie the puppets [i.e., the bamboo pole] securely into their waist band in front, leaving their hands free to work the puppet’s hands and heads [from below]. The head too is made mobile with strings [passing through the body], held [by the puppeteer] in a straw ring , which facilitates the hold for manipulation. Actually, there is not much movement in these puppets, but the puppeteers themselves jump and dance vigorously to produce the effect of movement. A Putul Nautch programme can be witnessed at fairs or festivals in villages and as they are no-tickets shows, like most of the Indian traditional puppet plays the puppeteers carry no regular stage. Usually they hire or get on loan a back-drop and a front curtain from the local theatre units. The front curtain is high enough to hide the manipulators and is fixed on bamboo poles, the backdrop is usually four metres in height, so it shows the puppets up clearly. However, on rare occasions, these puppet players have a box-like stage constructed from bamboos, with a painted cloth proscenium and a roof top of straw known as the Putul Ghar or House of Dolls.

Then there is the glove puppet, operated from below. Today, we find such puppets in all cultures. I believe the glove puppet originated directly from the rod puppet. In Indonesian and Chinese rod puppetry, the figures are dressed in cloth garments that hide the main support rod. In the Chinese type (see picture), the rods to control the puppet’s hands and arms are also hidden by being covered by the sleeves of the garment, and these rods extend down inside the robe to protrude underneath. The puppeteer, when clutching the main rod, keeps his hand hidden inside the clothing of the figure. It is a small step to abandon the rods and to use one’s own hand to manipulate the puppet directly, as is done with a glove puppet.

Chinese Rod Puppets

Very few records describe enough about the puppets referenced that we can determine what sort they are, i.e., string, glove, rod, or shadow puppet. Therefore, the date of introduction of the glove puppet is problematic.

And yet glove puppets may be very ancient. Speaight mentions the Greek word koree as meaning both a sleeve that covers the hand, and a small statue. A glove puppet encompasses both senses of the word.

Rajasthani string puppets, the Kathputli, are remarkable in their resemblance to glove puppets:

In the state of Rajasthan,…,which is in the northwest, string marionettes predominate. They are operated by members of a centuries-old subcaste of entertainers known as the kathputli bhats – the “wooden-puppet performers.”…Indian village puppet shows are played most often at night. The puppeteers work on the ground, standing behind a brightly colored cloth backdrop stretched between two poles, or perhaps between two upended charpoys – wooden bed frames. In front of the cloth, lined up elbow to elbow, is the cast of marionette characters, an assemblage commonly called the durbar, or court, the most important part of the Rajasthan setting. Their strings are wound around a length of bamboo at the top of the back cloth, and unwound when it is time for a particular character to go “on stage.” Oil lamps placed at either side light the figures. The audience is fanned out in front, seated on the ground…

All literary references to strings on the fingers of the puppet master are true in Rajasthan. The kathputli have only two strings. One running from the top of the head over the puppeteer’s fingers and back to the puppet’s waist supports it and allows it to bow and whirl. The other continuous string moves the hands. Such a simple control suggest simple results, but a sutradahar can be most eloquent. The warrior brandishes his sword and shield, the dancing girl delicately lifts the hem of her dress with the aid of pins at the tips of her fingers.

Furthermore, the way the marionette is constructed gives it a considerable degree of built-in activity. The head and body are carved from a solid piece of wood, often mango. The downward-curving arms are made of stuffed material that is quite springy, and, therefore, very good for the puppet’s fast fighting actions. No legs are needed. A pleated skirt, the marionette’s proudest garment, can suggest any manner of walking, running, or dancing. It is rather like a kilt, thin material weighted with borders of gold or silver cloth. The kilt has a life of its own, and a skilled operator can whirl it, spin it, spread it flat on the ground, or fill it with air like a balloon…

Certainly there is an element of the divine in the kathputli language, a wordless vocabulary of sounds that seems most appropriate for the small (eighteen- to twenty-inch) figures. This simple, effective language is produced by the head puppeteer with a bamboo-and-leather reed which he holds in his mouth and articilates by blowing through it and shaping his lips. Other later puppet cultures have attempted to improve on this technique by articulatiing real words through a “Punch whistle” – called “swazzle” in England and “pratique” in France – but the Indians accept it as a puppet language and let it go at that.

The Kathputli are the most primitive form of puppet operated from above. As mentioned, there is a reference to puppets worked by strings in the Buddhist Canon, the Therigatha of 100 BC. And Greece mentions them even earlier. It seems that in ancient Egypt, Greece, and India we have some of the earliest artifactual evidence of string-operated figures and toys, and some of the earliest literary references to puppets or automata.

The evidence indicates that puppetry began as a religious ritual, and, wherever puppet shows display this aspect, this tells us that that puppet theatre is probably of ancient lineage. It is to be noted that Western puppet theatre today is completely secular, yet in the beginning, many such shows had a definite ritual purpose, as indicated by Herodotus.

It would seem that puppets which developed from shadow theatre would necessarily be operated from below, and so it is an important problem how the string puppet evolved, a form operated from above. Again, the shadow theatre is a possible parent of this form. Many sorts of shadow puppets have used strings for manipulation. We may see that the European ombres chinoises (Chinese shadows) utilised strings to operate the figures. In Bali, strings are used in addition to the rods to affect different movements. And some shadow figures in India (the type that perform special tricks) have string operations. But more likely, it was from the automata that string puppetry developed.

There is a general sense that string puppets came before the shadow theatre, at least when we examine the historical documents and artifactual evidence. In addition, with primitive Man, ritual figurines were fashioned centuries before cave paintings ever appeared, and one of the starting points, in one theory, for the invention of shadow plays was drawings and paintings.

Shadow theatre is generally believed to be extremely ancient, notwithstanding that we find no absolute proof of the existence of shadow theatre until our era AD. Yet we cannot help but sense something very old about the shadow theatre in just its sheer simplicity. One can easily envision primitive Man casting shadows of his human ancestors in a ritual worship in front of his campfires. It is to be noted that the majority of shadow theatre forms display a human figure design much like the ancient Egyptian wall paintings. This resemblance is especially striking in the modern Balinese leather puppets (also called wayang kulit, as in Java). They both have the large and elaborate headdresses, the same eye shapes; the shoulders are frontal while the heads are in profile; the feet and legs are positioned one in front of the other also in profile. The general shape of the head and shoulders is remarkably similar to the Egyptian drawings (see example).

A Balinese Shadow Figure

While I do not suggest that the shadow theatre was invented by the ancient Egyptians, we can easily see that the design of the figures in almost all traditional shadow theatres is configured the same as when Man made drawings of himself and his kings starting in 3000 BC. Later, a development to more realistic human profiles, comes around 1367-1350 BC, with the Pharaoh Akhenaton.

Indeed, shadow theatre need not even utilise flat figures. A shadow play can be presented using doll (rounded) figures, but we see that this is not the case in traditional shadow theatres today, or even in the remote past. This seems another indication that the shadow play originated from drawings.

I believe that it was from the shadow theatre that the idea of performances of plays utilizing puppets originated. We see in the shadow theatre the true first puppet play, that is, a story told through acting.

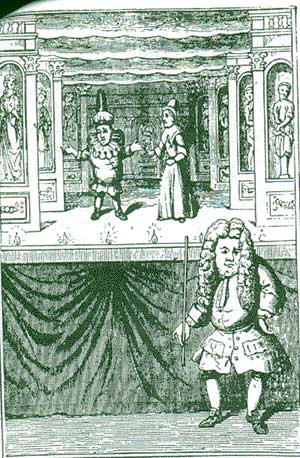

The early shadow theatres had a narrator who did not manipulate the puppets, and who stood in full view of the audience, outside the booth, explaining the action of the play, just as in the picture explanation shows which preceded it in development. Von Boehn mentions that early puppet shows in Europe had also this procedure of a interpreter: “In point of fact there is no real evidence that these puppets were introduced with dialogue at all; some historians, such as Magnin and Maindron, are of the opinion that the puppets appeared only in pantomime, and that a man in front of the stage related the course of action.” George Speaight affirms, in The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1995 edition, under the entry “Puppetry”, that “In many forms of puppet theatre,…the dialogue is not conducted as if through the mouths of the puppets, but instead the story is recited or explained by a person who stands outside the puppet stage to serve as a link with the audience. This technique was certainly in use in England in Elizabethan times, when the ‘interpreter’ of the puppets is frequently referred to; this character is well illustrated in Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair, in which one of the puppets leans out of the booth (they were hand puppets) and hits the interpreter on the head because it does not like the way he is telling the story.” In addition, J. P. Collier, the famous author of Punch and Judy, wrote that “The manner in which puppet-shows were represented in Spain, is very clearly described in chap. 26 of the second part of ‘Don Quixote’ [sixteenth century]. Peter there worked the figures, and his boy interpreted, though not to the knight’s satisfaction.” (See pictures for examples of a narrator in puppet shows.)