(Paper presented by Keith Rawlings at the UNESCO-APPAN Symposium and Festival. Puppets – Facing the Interior Face – Memory, Recovery and Transposition: The Asian Experience. Bangkok, Thailand 5 – 10 June 2004)

(A) “Puppet” Remains and Other Evidence

THE WEST

1) This very ancient articulated figure was discovered in Brno, Czechoslovakia and is the earliest puppet in existence, dated, incredibly, 26,000 years ago (!). It is now housed in the American Natural History Museum in New York City. It has tiny holes for tying together the limbs, and is fashioned from mammoth ivory. It is even nicknamed “the marionette” by archaeologists. We do not know the application of this figure. A toy, a doll? An ancestor figure? An amulet? Is it a puppet? Yes it is, if we define “puppet” as an articulated figure.

Two views of the figure

2) An ancient Egyptian string-pulled figure in the act of kneading bread, dated 2000 BC.

Was it used as a toy? Or as a slave-figure for the afterlife? This can be called a puppet.

3) Ancient Egyptian figures of dwarfs on a platform pulled by strings.

Was it a toy? Dated from the 12th Dynasty (c. 1991 – 1783 BC).

4) Ancient Egyptian dolls. [2000 BC]

Definite toys.

All figures to be considered as dolls must be:

Female – for young girls (male dolls are very rare)

Articulated – for play – at first just the arms were moveable, then all the limbs

Nude – to be dressed

If there are holes in the skull for attaching hair, these are more sophisticated dolls, and of later date.

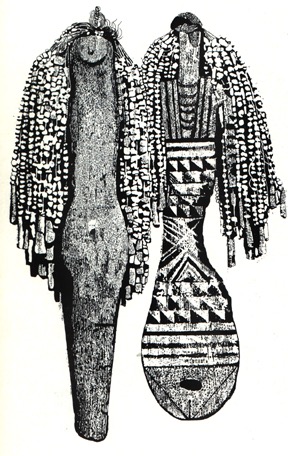

5) Egyptian Paddle dolls. [2000 BC]

These seem to have been very small. One in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is quite tiny. Their use was probably funerary – for the afterlife. They are inscribed with fertility symbols. Their design must be traditional, so these figures may originally date back to an earlier period than 2000 BC.

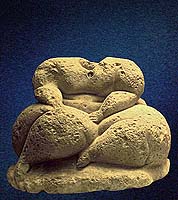

6) Malta – stone goddess (head lost) [2000 BC]

Many of these were found in Malta, with a socket between the shoulders for the head and also with small holes for manipulating a cord or string. It is thought that the heads of these figures, which are almost always missing, were made from other materials, possibly even wax. They were probably oracle figures.

7) Ancient Greek dolls.

Definite toys.

The earliest Greek dolls seem not to have been influenced by Egypt’s, as they were at first much more primitive (see figures at right). Plus they had articulated legs rather than arms at the beginning. The earlier Egyptian dolls, by contrast, had articulated arms rather than legs.

Later, they became more realistic, and fully articulated. Was this influence from Egypt?

As we approach the era AD, Roman dolls started becoming less sophisticated and cruder again, likely due to the causes of the fall of Rome.

CONCLUSION: No proven theatrical or entertainment puppets were ever discovered from ancient times – probably because they were made of wood and cloth (hence perishable). Many wooden and cloth objects have been preserved from Ancient Egypt, but no evidence of a puppet theatre (Egypt has a very dry climate – many wooden dolls and some rag dolls were preserved). Possibly Greece and Rome had a puppet theatre (seen from textual evidence) but the wetter climates they possess do not allow wood and cloth to preserve well, so no evidence of how puppets were shown to the public in ancient Greece and Rome is currently available.

THE EAST

1) Harrapan articulated, stringed figures of animals [2500 BC] – crude, so probably toys – terra cotta, clay

2) Another Harrapan articulated figure – this time human (possibly male, note hole for phallus) – use? – very sophisticated sculpturally

3) An ancient Indian articulated figure of ivory, dated before the 2nd century BC.

Is it a doll? Yes, since it is also nude and female. Plus it seems to have holes in its skull for attaching hair. These early Indian figures – were they influenced by the civilization of Egypt?

4) A figure from China c. 107 BC.

Very large (6 ft. 2 inch), and fully articulated. Could sit, stand, or kneel. Note the realistic head, yet the body is only a frame. It was obviously made to be clothed. Is it the earliest Bunraku type of puppet? Was it manipulated as like a ventriloquist doll, from behind?

5) A Chinese puppet-like figure [Han Dynasty, 206 BC – 220 AD] housed in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

The head seems to be moveable, and the hands, though now missing, must have been moveable also, as we see the two holes made for them. Also note two other holes at the back of the figure, which is hollow. The top opening must have been for controlling the head, and the bottom one for the hands. As the holes are too small to insert a person’s hands, I suspect long sticks must have been used to assist in the figure’s manipulation, from the back. It is labeled a Female Attendant, mortuary figure. But we do not know in what manner it was used or for what exact purpose it served.

In China it seems there was no influence from the West, as China’s earliest puppet figures are very different in concept and purpose.

CONCLUSION: Puppets certainly are extremely ancient, as asserted by many scholars. Prehistoric humans must have invented the art of articulated figures many thousands of years ago, and spread the tradition of making them world-wide in their migrations around the entire planet.

A recent book (2002) “The Roots of Theatre: Rethinking Ritual and Other Theories of Origin” by Eli Rozik, questions the widely held theories of the ritual origins of theatre. His book proposes that rituals which seem to be evidence of early theatre may actually be only instances of ritual practitioners using already-existing theatrical techniques in their rituals. Mr. Rozik argues very convincingly and proposes instead that the human roots of theatre are “the innate faculty of imagistic thinking.” This has immense implications for theories of the origins of puppets, which too are almost universally thought of as originating in ritual.

(B) Wayang, Nang Yai, Sbek Thom, Ying Hsi, Chhayanataka – Indian and Chinese “evidence” of origins

To test an Indian origin of shadow plays we must study the wayang of Java, said to be the place of the earliest shadow plays in SE Asia, from whence all SE Asian shadow theatres spread.

Today, “wayang”, when coupled with other words, has several meanings – but standing alone, does it really mean “shadow play/puppet”? This is a basic assumption of many scholars, but it is never discussed why they accept that the word “wayang” by itself, mentioned in the earliest texts, means “shadow puppets” or “the shadow play.”

Old copper plates of Kuti (Jaha), in Java dated 840 AD:

“Aringgit” is mentioned on plate 6 but with no description, and used amongst a list of other kinds of performers. The word “ringgit”, is always said by many scholars to be synonymous with “wayang”. But does “ringgit” really mean “wayang”? Some of the senses of “ringgit” are “milled or serrated”, “jagged or toothed” (i.e., cut out) [WILKINSON]. So then the meaning of “ringgit” as a “leather cut-out puppet” follows easily. As it also means “dancing girl” [WILKINSON], we may ask how did that additional meaning come about? It is said that Javanese dancers in the wayang topeng and wayang wong, generally mimic the movements of the flat leather figures as in a wayang shadow play, so “ringgit” meaning “dancer acting as a puppet” is quite logical. It now follows that “ringgit” probably originally referred to the puppets of the wayang (“cut-out”), then later the meaning was expanded to refer to the shadow play itself.

Although on the inscription there is also mention of “all sorts of servants of the inner apartments” hailing from several places in India (!) and SE Asia, we cannot really connect these foreign servants to the “aringgit” in this copper plate.

Old copper plates of Central Java by King Balitung dated 907 AD:

There are two translations of the “mavayang” (performing wayang) section of this plate:

1- Si Nalu recited the Bhimakumara, dancing like Kicaka; Si Jaluk recited the Ramayana, blowing flutes and making buffoonery; Si Mungmuk (and) Si Galigi showed vayang in honour of [the] gods and presented (above all) Bhimaya-Kumara [SARKAR].

2- Si Nalu recited Bhima Kumara (and) danced as Kicaka; Si Jaluk recited the Ramayana; Si Mukmuk play-acted and clowned; Si Galigi performed wayang for the gods, reciting the story of Bimma Kumara [SOEDARSONO].

The first translation has two “vayang” performers Si Mungmuk and Si Galigi (is it the puppeteer [dalang], and an assistant?), but the second translation has only Si Galigi performing “vayang”. It appears to be partly a ritual performance “for the gods”, telling a story about Bhima from the Mahabharata, and staged along with other performances and entertainments. The other performers are clowns, musicians, human actors, and dancers, and there is no connection to the word “mavayang”, so the wayang performance here must be different than any of these other performances: it’s not a dance, not a farce, and not a (human) play. But is it the shadow play?

The Balinese Wangbang Wideya written during Majapahit times mentions wayang performances several times, and gives detailed descriptions. It is very clear in this work that they are speaking of wayang kulit shows, and the word “wayang” by itself is used to refer to the puppets themselves and the wayang kulit play. So it seems that, very early, “wayang” by itself DID mean “shadow play”, and is not a convention of modern times. It may be that, later, when other forms of wayang shadow shows proliferated, or, after the wayang shadow plays outstripped all other entertainments in popularity, it was necessary to qualify the different kinds of shows with separate “wayang” names, that is, wayang beber, wayang kulit, wayang golek, wayang wong, etc.

Another fundamental question is: does the Javanese, Balinese, and Malay word “wayang” really come from the Malay word “bayang” meaning “shadow”? The author of our English translation of the Wangbang Wideya says that “widu” (singer) in Javanese is cognate with “bidu” (singer) in Malay [ROBSON]. So these differences in the languages support the etymology that Javanese, Balinese, and Malay “wayang” really is equivalent to Malay “bayang” meaning “shadow”.

We can now conclude, then, that these two texts must indeed refer to the shadow play. However, on the one dated 840 AD, even though at the end of the text it is inscribed “written in Maj(h)apahit” – contradicting the date 840 AD at the beginning – it is still considered by some scholars to be a copy of a 9th century original. These plates were discovered by a local Javan and sold to the Batavia Society in 1866 for a price. At first only 10 plates were found, but one plate (no. 7 of 11) was missing, and the same person later found it, for which he was also paid. In addition, the language on the plates is very corrupt (is it perhaps because they are copies of copies of copies?), and some scholars thought the language in it was “rather new”, meaning “rather modern”. All these facts make them possibly fakes to be disregarded.

The Indian evidence of words referring to early shadow plays: Mahabharata: “rupopajivana”, Therigatha: “ruparupaka”, Mahabhasya: “sobhika”, Dutangada: “chhayanataka” – all are much debated and there is no agreement on the meaning of any of these terms. Only in the Mahavamsa where there is mention of showmen of “camma-rupa” (leather figures) do we seem to have a clear reference to leather puppets in Sri Lanka (the players were Tamil spies), in the 11th century.

M.V. Ramana Murty mentions an Indian text Andhra Sarwawamu where “it is stated that the Pallava kings and the Kakatiya kings, in the sixth century when they brought the group of island of Yava (now known as Indonesia) under their control, introduced the leather puppetry of South India into Indonesia.” Mr. Murty does not give any particulars about or quotations from this text so I have not been able to check this reference, but, if authentic, then we have here real evidence of an Indian origin of wayang.

Buddhaghosa’s commentary (4th century AD) on the mention of the term “caranam nama cittam” in the Samyutta-Nikay says:

There are Brahmin sectaries whose general name is Nakha. They have a (movable or portable) picture gallery made, roam about with it, exhibiting thereon the various kinds of representation of happy or woeful states of existence according to good or bad destinies….[MAIR]

“Movable picture gallery”: is this possibly a shadow theatre booth? Displaying pictures inside a cloth booth as in a museum gallery (as this text is normally interpreted) seems to me unlikely at this early date. It is to be noted that shadow puppets are frequently referred to in India as “leather pictures”. In fact, Mr. Murty gives us another name for the Tholu Bommalata shadow theatre of Andhra Pradesh: Chaya Charma Chitra Natakam, which means “shadow leather picture show”. So if the above interpretation of Buddhaghosa is accepted, then the earliest certain mention of shadow plays for India is in the 4th century, making it earliest of all for shadow theatre, and giving the priority of this theatrical to India.

Indian “chhaya” = Indonesian “wayang”? Note that “chhaya” can mean both “shadow” and “puppet” in Sanskrit, as does “wayang” [MAIR].

Could Thai “nang yai” = Chinese “nung ying hsi” (performance [“nung”] of shadow play [“ying hsi”])?

In Cambodian “nang sbek thom”, “nang” means “leather”, but so does “sbek” (“thom” means “large”). Why are there two words meaning “leather”? Perhaps “nang” means “leather” and also “performance”, somewhat like “wayang” means “a puppet” and also “a play”? This then brings it in line with the Chinese word “nung”.

“Wayang”-like Chinese words:

“ang” meaning “puppet” and “medium” [PLOWRIGHT] = “wayang” (puppet), “dalang” (medium)?

“ying/yang” (“shadow/light”) = “wayang” (“shadow”)?

“phe ang” = “leather puppet” in Chinese [SCHLEGEL] – sounds like “wayang”, which also means “leather puppet”.

The earliest mention of the nang yai in Thailand comes from The Code of the Palace Guards in 1458. Rene Nicolas says:

It is a kind of Palatine law which treats of the duties of civil servants, men and women of the royal house and which specifies the details of the various ceremonies. At the occasion of each of these ceremonies, entertainments took place, sometimes lasting 7 days, sometimes for 15, sometimes a month, and the different diverse amusements practiced are then mentioned at length. It says that one sees tightrope walkers, sword swallowers, alternating songs, recitations of the Sepha or Niyai, different dances etc., without forgetting the Nang which seems to hold an important position in the festivals and that the Code in question mentions on several occasions: for example at the time of the capture of a white elephant “there are eight Nang theatres”, further: “one plays the Nang ram”, and “there are two Nang theatres”, or again “one plays the Nang with artificial fires” etc. As this text is absolutely authentic, we are justified in affirming that the shadow theatre formed part of the usual spectacles and even the rituals of the Siamese during the early part of Ayuthia period.

One Chinese text says the following.

…Sometimes there were plays in smaller mansions, with people acting Great Shadow Shows (ta ying-hsi), and the children clamouring incessantly all evening…[DOLBY]

This mention of “people acting Great Shadow Shows…” is thought by some scholars [DOLBY, BROMAN] to mean “people acting as shadow puppets”, but perhaps it means dancers appearing with large leather puppets in front of and behind the screen, like Thai “nang yai” and Cambodian “sbek thom”? If this is correct, then we have here a “nang yai/sbek thom”-like performance dated 1280, which date is much before the earliest mention of the nang in Thailand.

There is another Chinese text mentioning performances (“nung”) of “ch’iao ying-hsi”, where “ch’iao” means “tall, feigning, feign, deceptive, etc.” [DOLBY]. The meaning “tall” could be applicable here, and if so it is another reference to “tall (or large) shadow show”, and it is dated even earlier (1147). Is the Chinese Great Shadow Show the origin of “sbek thom” and “nang yai”? Khmer and Thai large shadow figures do not exist elsewhere in SE Asia – they are unique – they do not seem to have come from Java. It may be significant that Cambodia and Thailand are on the mainland with China.

If we ignore or disbelieve the Javanese copper plates mentioned above as earlier evidence of wayang shadow plays, it can be imagined that the technique of the shadow play was brought to Java by the Chinese, but indirectly through the Mongols, in the 13th century. Indeed, it is asserted by many scholars of the shadow theatre that this type of theatrical was known and spread by Ghengis Khan’s armies. Apparently, “Ghengis Khan enjoyed watching shadow puppet plays during lulls in the fighting” [JILIN], but this has never been satisfactorily documented. In any case, Chinese annals describe Ghengis’ grandson, Khubilai Kahn’s, forays in Java in the 13th century:

Khubilai Khan…was not pleased by Javanese hegemony in the straits. In 1289 he sent envoys to [King] Kertanagara [of Java] to confront him and demand that the tribute missions be sent from Java to the Khan’s capital. Kertanagara replied by disfiguring and tattooing the faces of the Mongol envoys, and sending them back in this disgraced fashion. His impudence so enraged Khubilai Khan that the Mongol sent 1000 warships to chastise Java.

However, before the fleet arrived, the previously subordinated ruler of Kadiri [a kingdom in eastern Java] defeated Singhasari [another kingdom in eastern Java] in 1292, and during the occupation of the royal residence of Singhasari, King Kertanagra died. After this calamity in the last months of 1292 or early 1293, Kertanagara’s son-in-law Raden Vijaya cleared a new capital site from the forest, and named it Majapahit. This royal city, which gave its name to the realm, was located about fifty kilometres upriver from Surabaya, a little southeast of present-day Majakerta….

When the Mongol warships arrived, the son-in-law managed to persuade them that Singhasari was gone and that since Kertanagara had died, which was punishment enough, that they should help him chastise Kadiri’s ruler instead. It was only after he had destroyed his local rivals and enemies with the help of the expeditionary army, that he turned on the Mongols and forced them to evacuate Java. [HALL]

Of course, the fact that Khubilai’s armies came to Java in such large numbers, means they brought their own equipment, supplies, and likely even their own entertainers for the troops. The mingling and interaction of the two cultures during this short period, if the Mongol shadow theatre figured in it, may be the origin of wayang in Java. But I believe that India is still the most likely source of Indonesian shadow plays.

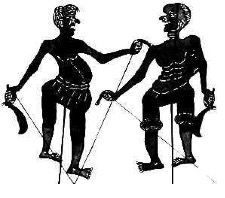

Two ancient Chinese pictures

(1) This is a picture inscribed at the back of a bronze mirror from the Song Dynasty [960 – 1227 AD] It is preserved in the China History Museum in Beijing. But it is probably a puppet play, not a shadow play. It looks like the puppeteer is holding 3-dimensional (not flat) figures, and is seemingly displaying them above the top of the screen. If this is supposed to be a shadow play, the artist did not depict its characteristics correctly.

(2) This is one of the frescos in the Wenshu Palace of the Yanshan Temple in Fanzhi, Shanxi Province, painted during the Dading period (1161-1189) of the Jin Dynasty. It is definitely a shadow play. The screen is tilted forward at the top as in India, Java, Bali, Malaysia, etc., it is very small and portable, and there is only one performer. The figures are very small and not articulated. Neither do they seem to be of transparent dyed leather or perforated. There are no sticks for manipulation of the figures, which are held by the bottom part, and it seems to have been a children’s show. There is no lamp in evidence, and no musicians. One child seems to be playing with the puppeteer’s unused figures off to the side while watching the puppeteer, seemingly trying to imitate the performer – unless this person is the puppeteer’s assistant. There is nothing ritualistic or religious about it – it is pure entertainment. This is the earliest artistic depiction of a shadow play performance. This may have been the earliest way of presenting the wayang, too.

In Mayasia, the dalang or shadow puppeteer of the wayang is hidden from the audience along with the musicians, singers, and assistants, by a structure called a panggung, which is an elevated temporary platform, enclosed on three sides by twisted bamboo strips or mats, and on the fourth by a kelir, or screen [HOOYKAAS]. These terms, kelir and panggung, are identical in Malaysia, Java, and Bali, but today in Java the musicians, singers, assistants, and even the dalang are all visible to the audience, there being no enclosed structure or platform, and the show being given in open space. That this was not the case earlier in Java is evidenced by the Old-Javanese text Tantu Panggelan (1500 AD) where it is stated shadow players had a panggung (elevated, enclosed platform), and this structure is also mentioned in the Balinese Wangbang Wideya in connection with wayang kulit. If the Javanese and Balinese still used the panggung in 1500 AD, then who invented the highly portable apparatus as seen in the old Chinese fresco of 1100 AD above? Today the open-space type of show is now much more common.

CONCLUSION: The evidence of shadow plays in the old texts indicates that shadow theatre may not be as ancient as are puppets and articulated figurines, and in fact may not be the most ancient of all puppet forms, as is sometimes asserted. It seems to be a somewhat complicated concept to arrive at, relative to ordinary puppetry, and probably developed as another form of puppetry early in the Christian era, certainly in the East. It appeared all over the Asia (even as far as Arabia) by the 11th century, indicating rapid migrations of shadow puppeteers throughout the East, and the instant popularity and adoption of this form in many different and widely separated countries. As P. L. Amin Sweeney has said, a person has only to witness a shadow play once to grasp the technique. Any foreigner in another country can then create shadow plays once returning to his or her homeland. These new shadow plays will then appear to be indigenous creations.

(C) Sutradhars,“string holders”, and temple architects

The theory that puppet plays were prevalent before human theatre is hinged on the Sanskrit word “sutradhar”, literally “string holder”, to refer to a “play director”. But in ancient Egypt the phrase “holds the string” was a ritual term meaning “to found a temple” [FOUCART], the same as in India (“sutradhar” has many meanings in India). Coincidence or influence? It seems a person who held a string to measure the theatre or temple before it was built was the origin of the connection between the “string holder” and the “theatre architect”. So to name the theatre director of Sanskrit plays “the holder of the strings, sutradhar”, may actually not refer back to the puppet play, but instead to the “(temple or theatre) architect”, then “architect of the play”, thence “play director”.

The earliest mention of a sutradhar is not in the 10th century as says Ridgeway, but in the Natyasastra (c. 200 BC – 300 AD), or Treatise on Dramaturgy. The meaning of the term there was “play director”. So this places the sutradhar contemporary with ancient Greece and Rome.

CONCLUSION: The theory that human theatre developed out of puppet performances seems unlikely. Human theatre is a worldwide phenomenon and may have several origins. In the East, certainly puppets have greatly influenced human theatre (as clearly seen in India, China, Burma, and Japan), but probably did not “cause” it. We see this in the Japanese Bunraku, which did not appear before the Kabuki theatre, but powerfully influenced it at a certain period.